IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR) 2019

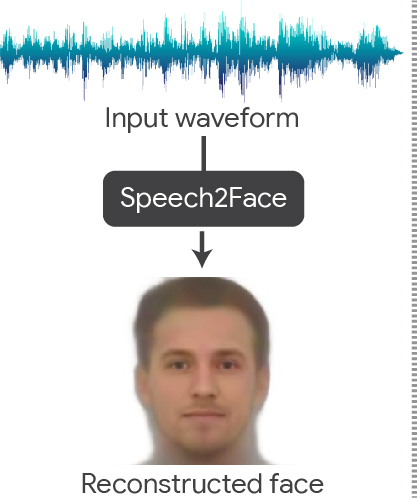

Speech2Face: Learning the Face Behind a Voice

| Tae-Hyun Oh* ✝ | Tali Dekel* | Changil Kim* ✝ | Inbar Mosseri | William T. Freeman✝ | Michael Rubinstein | Wojciech Matusik✝ |

|

✝ MIT CSAIL |

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

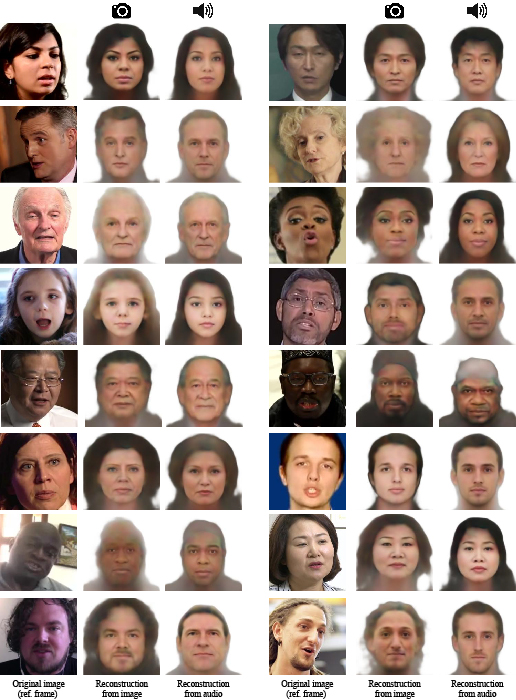

We consider the task of reconstructing an image of a person’s face from a short input audio segment of speech. We show several results of our method on VoxCeleb dataset. Our model takes only an audio waveform as input (the true faces are shown just for reference). Note that our goal is not to reconstruct an accurate image of the person, but rather to recover characteristic physical features that are correlated with the input speech. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Abstract

How much can we infer about a person's looks from the way they speak? In this paper, we study the task of reconstructing a facial image of a person from a short audio recording of that person speaking. We design and train a deep neural network to perform this task using millions of natural videos of people speaking from

Internet/Youtube. During training, our model learns audiovisual, voice-face correlations that allow it to produce images that capture various physical attributes of the speakers such as age, gender and ethnicity. This is done in a self-supervised manner, by utilizing the natural co-occurrence of faces and speech in Internet videos, without the need to model attributes explicitly.

Our reconstructions, obtained directly from audio, reveal the correlations between faces and voices. We evaluate and numerically quantify how--and in what manner--our Speech2Face reconstructions from audio resemble the true face images of the speakers.

Paper

Supplementary Material

|

[Link] |

Ethical Considerations

|

Although this is a purely academic investigation, we feel that it is important to explicitly discuss in the paper a set of ethical considerations due to the potential sensitivity of facial information. |

||

|

Privacy. As mentioned, our method cannot recover the true identity of a person from their voice (i.e., an exact image of their face).

This is because our model is trained to capture visual features (related to age, gender, etc.) that are common to many individuals, and only in cases where there is strong enough evidence to connect those visual features with vocal/speech attributes in the data (see ``voice-face correlations'' below). As such, the model will only produce average-looking faces, with characteristic visual features that are correlated with the input speech. It will not produce images of specific individuals. | ||

|

Voice-face correlations and dataset bias. Our model is designed to reveal statistical correlations that exist between facial features and voices of speakers in the training data. The training data we use is a collection of educational videos from YouTube, and does not represent equally the entire world population. Therefore, the model---as is the case with any machine learning model---is affected by this uneven distribution of data. More specifically, if a set of speakers might have vocal-visual traits that are relatively uncommon in the data, then the quality of our reconstructions for such cases may degrade. For example, if a certain language does not appear in the training data, our reconstructions will not capture well the facial attributes that may be correlated with that language. Note that some of the features in our predicted faces may not even be physically connected to speech, for example hair color or style. However, if many speakers in the training set who speak in a similar way (e.g., in the same language) also share some common visual traits (e.g., a common hair color or style), then those visual traits may show up in the predictions. For the above reasons, we recommend that any further investigation or practical use of this technology will be carefully tested to ensure that the training data is representative of the intended user population. If that is not the case, more representative data should be broadly collected. |

||

|

Categories.

In our experimental section, we mention inferred demographic categories such as "White" and "Asian". These are categories defined and used by a commercial face attribute classifier (Face++), and were only used for evaluation in this paper. Our model is not supplied with and does not make use of this information at any stage. |

Further Reading

"Seeing voices and hearing faces: Cross-modal biometric matching", A. Nagrani, S. Albanie, and A. Zisserman, CVPR 2018 "On Learning Associations of Faces and Voices", C. Kim, H. V. Shin, T.-H. Oh, A. Kaspar, M. Elgharib, and W. Matusik, ACCV 2018 "Wav2Pix: speech-conditioned face generation using generative adversarial networks", A. Duarte, F. Roldan, M. Tubau, J. Escur, S. Pascual, A. Salvador, E. Mohedano, K. McGuinness, J. Torres, and X. Giroi-Nieto, ICASSP 2019 "Disjoint mapping network for cross-modal matching of voices and faces", Y. Wen, M. A. Ismail, W. Liu, B. Raj, and R. Singh, ICLR 2019 "Putting the face to the voice: Matching identity across modality", M. Kamachi, H. Hill, K. Lander, and E. Vatikiotis-Bateson, Current Biology, 2003 |

Acknowledgment

|

The authors would like to thank Suwon

Shon, James Glass, Forrester Cole and Dilip Krishnan for

helpful discussion. T.-H. Oh and C. Kim were supported by

QCRI-CSAIL Computer Science Research Program at MIT.

|